Conjurors

KeskusteluSkeptics and Rationalists

Liity LibraryThingin jäseneksi, niin voit kirjoittaa viestin.

Tämä viestiketju on "uinuva" —viimeisin viesti on vanhempi kuin 90 päivää. Ryhmä "virkoaa", kun lähetät vastauksen.

1CliffordDorset

I read once that conjurors and illusionists find scientists to be the more gullible. Does this apply equally to skeptics?

2darrow

I assume that this applies only when the scientist of skeptic does not know that a conjuror is at work. They expect objects to obey natural laws and not appear or disappear randomly and if secretly misled that could be interpreted as gullibility. I doubt that your assertion applies when they know they are in the presence of a conjuror.

4Helcura

It may actually be true though, as many scientists can be very focused, and stage magic works by getting the audience to focus strongly on one thing and fail to notice another thing.

5thorold

>1 CliffordDorset:,3

I think we need to get Clifford back to explain the original question. Are you asking whether conjurors find skeptics to be more gullible than the average bear? - or whether skeptics find scientists to be more gullible TTAB? Or scientists skeptics...

I think we need to get Clifford back to explain the original question. Are you asking whether conjurors find skeptics to be more gullible than the average bear? - or whether skeptics find scientists to be more gullible TTAB? Or scientists skeptics...

6darrow

I think we can safely assume that he means more gullible than humans who are not scientists or skeptics.

7CliffordDorset

>3 Booksloth:, 5

Sorry to be vague on this one. 'More' was intended to imply 'more for one who had a reputation as a scientist than one who didn't'.

And sorry that I cannot provide chapter and verse. Being a scientist I probably had more pressing tasks than noting chapter and verse at the time. It's possible it was Harry Houdini, but also that it might have been one of the Victorian drawing room table rappers of photo foggers. I felt that others might have noted the assertion.

Speaking for myself, I do think that scientists have a general propensity to accept what they observe either visually or with the other senses, before embarking on an investigation to collect more observations from other points of view. I believe that this is the true nature of science. Non-scientists - those without the rigour of a real scientific grounding - may perhaps be more likely to dismiss what they see as 'contrary to common sense'. For me, science is the practice of adding to common sense rather than accepting it as complete. The most interesting parts of observations are those which appear contrary to accepted knowledge.

Sorry to be vague on this one. 'More' was intended to imply 'more for one who had a reputation as a scientist than one who didn't'.

And sorry that I cannot provide chapter and verse. Being a scientist I probably had more pressing tasks than noting chapter and verse at the time. It's possible it was Harry Houdini, but also that it might have been one of the Victorian drawing room table rappers of photo foggers. I felt that others might have noted the assertion.

Speaking for myself, I do think that scientists have a general propensity to accept what they observe either visually or with the other senses, before embarking on an investigation to collect more observations from other points of view. I believe that this is the true nature of science. Non-scientists - those without the rigour of a real scientific grounding - may perhaps be more likely to dismiss what they see as 'contrary to common sense'. For me, science is the practice of adding to common sense rather than accepting it as complete. The most interesting parts of observations are those which appear contrary to accepted knowledge.

8Booksloth

#7 Thanks for the clarification Cliff.

I understand a bit more of what you're saying but I'm still having trouble getting my head around the idea that sceptics are gullible when, to me, the words mean the very opposite of one another. That's not to say that a sceptic might not question something, investigate it and become convinced of the wrong explanation - I'm quite sure that happens to us as much as it does to anyone else - but it is still surely that need to make our own investigations and to question the 'obvious' answers that makes us sceptics in the first place?

I understand a bit more of what you're saying but I'm still having trouble getting my head around the idea that sceptics are gullible when, to me, the words mean the very opposite of one another. That's not to say that a sceptic might not question something, investigate it and become convinced of the wrong explanation - I'm quite sure that happens to us as much as it does to anyone else - but it is still surely that need to make our own investigations and to question the 'obvious' answers that makes us sceptics in the first place?

9jjwilson61

No, scientists are supposedly gullible. They generally don't expect people to be trying to trick them. A skeptic on the other hand is prepared to deal with dishonest people. Some scientists are skeptics in that sense but not all.

10LolaWalser

#9

That must be the weirdest dumb generalisation about scientists yet.

#7

Speaking for myself, I do think that scientists have a general propensity to accept what they observe either visually or with the other senses, before embarking on an investigation to collect more observations from other points of view. I believe that this is the true nature of science.

You may believe what you wish, but it doesn't make it so. It is the stark opposite of everything I know about scientists and doing science.

That must be the weirdest dumb generalisation about scientists yet.

#7

Speaking for myself, I do think that scientists have a general propensity to accept what they observe either visually or with the other senses, before embarking on an investigation to collect more observations from other points of view. I believe that this is the true nature of science.

You may believe what you wish, but it doesn't make it so. It is the stark opposite of everything I know about scientists and doing science.

11southernbooklady

Isn't a scientist's job to be constantly asking "why is this so?" That's hardly an attitude I associate with gullibility.

That said, I think that science is sometimes gullible within its own ranks--they trust the authority of the process even when the results are counter-intuitive. I remember growing up when medical research determined that children should stop drinking milk after a certain (very young) age. I don't remember the reasons given--something about it not being natural to drink milk after being weaned, and that increased the risk of developing allergies or something? --

Anyway, my mother, not one to be overawed by doctors, said what a load of crap and gave us milk. Only to have her common sense justified years later when another group researchers determined that children who didn't drink milk had lower density bones.

That said, I think that science is sometimes gullible within its own ranks--they trust the authority of the process even when the results are counter-intuitive. I remember growing up when medical research determined that children should stop drinking milk after a certain (very young) age. I don't remember the reasons given--something about it not being natural to drink milk after being weaned, and that increased the risk of developing allergies or something? --

Anyway, my mother, not one to be overawed by doctors, said what a load of crap and gave us milk. Only to have her common sense justified years later when another group researchers determined that children who didn't drink milk had lower density bones.

12LolaWalser

#11

Doctors are rarely scientists, and medicine is NEVER science.

Doctors are rarely scientists, and medicine is NEVER science.

13reading_fox

# "Only to have her common sense justified years later when another group researchers determined that children who didn't drink milk had lower density bones."

The two are not related though - if you'd had a supply of calcium from other non-milk sources you may (I haven't seen the evidence so don't know) have been even better off not having had the milk. Science is tricky like that with confounding factors everywhere.

The two are not related though - if you'd had a supply of calcium from other non-milk sources you may (I haven't seen the evidence so don't know) have been even better off not having had the milk. Science is tricky like that with confounding factors everywhere.

14jjwilson61

10> That must be the weirdest dumb generalisation about scientists yet.

It's not originally my generalization. I remember being introduced to the meme during the Uri Geller fad. From Wikipedia:

Geller's performances of drawing duplication and cutlery bending usually take place under informal conditions such as television interviews. During his early career he allowed some scientists to investigate his claims. A study by Stanford Research Institute (now known as SRI International) conducted by researchers Harold E. Puthoff and Russell Targ concluded that he had performed successfully enough to warrant further serious study, and the "Geller-effect" was coined to refer to the particular type of abilities they felt had been demonstrated

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uri_Geller#Scientific_testing

And here's a fun quote from Agatha Christie I ran across while googling:

“Wharton: Nobody's so gullible as scientists. All the phony mediums say so. Can't quite see why.

Jessop: Oh, yes, it would be so. They think they know, you see. That's always dangerous.

It's not originally my generalization. I remember being introduced to the meme during the Uri Geller fad. From Wikipedia:

Geller's performances of drawing duplication and cutlery bending usually take place under informal conditions such as television interviews. During his early career he allowed some scientists to investigate his claims. A study by Stanford Research Institute (now known as SRI International) conducted by researchers Harold E. Puthoff and Russell Targ concluded that he had performed successfully enough to warrant further serious study, and the "Geller-effect" was coined to refer to the particular type of abilities they felt had been demonstrated

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uri_Geller#Scientific_testing

And here's a fun quote from Agatha Christie I ran across while googling:

“Wharton: Nobody's so gullible as scientists. All the phony mediums say so. Can't quite see why.

Jessop: Oh, yes, it would be so. They think they know, you see. That's always dangerous.

15LolaWalser

And that's enough for such a generalisation?

16LolaWalser

On Googling:

Just to be clear--"Stanford Research Institute" had/has nothing to do with Stanford University; H. Puthoff seems to be a "type", having been a Scientologist as well, Targ likewise had/has lifelong interest in "paranormal activity" and psychic phenomena, the pair got money (25 million bucks, in 1970ish? Wowee!) from the CIA/DEA for a 23-year long project into... let's just call it "this"--you know, I'm not sure "gullible" is the word to describe them.

Just to be clear--"Stanford Research Institute" had/has nothing to do with Stanford University; H. Puthoff seems to be a "type", having been a Scientologist as well, Targ likewise had/has lifelong interest in "paranormal activity" and psychic phenomena, the pair got money (25 million bucks, in 1970ish? Wowee!) from the CIA/DEA for a 23-year long project into... let's just call it "this"--you know, I'm not sure "gullible" is the word to describe them.

18MartyBrandon

The idea that scientists are actually more gullible than the average Homo sapien makes me wince a little, yet, I've known many and can see how it might be the case. They're often so very focused on a small sliver of knowledge that they have difficulty when put into an unrelated domain. And their commitment to the scientific method makes the handholds of their psychology transparent to the deceiver. Combine that with perhaps an above-average tendency for arrogance at having obtained a certificate certifying their great wisdom, and it's in some ways the perfect storm for a takedown.

The first time I heard the observation described was in an interview with James Randi (aka "The Amazing Randi"). Randi has this to say:

They think logically, from a cause-and-effect paradigm. A trickster supplies all the misdirection, the elements expected by logical inference, the necessary aspects that identify a situation as normal – then he uses a different approach, a set of actions, a scenario that leads the dupe to accept that the expected situation is being fulfilled – but it’s not. The scientist’s conclusion is that nature – which he/she knows does not change the rules to deceive – has been abrogated in some way. In other words, it’s magic…. Scientists assume that someone not thinking logically, cannot deceive them because he’s not their intellectual equal. They think they’re smarter than the con man, not recognizing that such deception is the strength of the con man, his only profession.

The first time I heard the observation described was in an interview with James Randi (aka "The Amazing Randi"). Randi has this to say:

They think logically, from a cause-and-effect paradigm. A trickster supplies all the misdirection, the elements expected by logical inference, the necessary aspects that identify a situation as normal – then he uses a different approach, a set of actions, a scenario that leads the dupe to accept that the expected situation is being fulfilled – but it’s not. The scientist’s conclusion is that nature – which he/she knows does not change the rules to deceive – has been abrogated in some way. In other words, it’s magic…. Scientists assume that someone not thinking logically, cannot deceive them because he’s not their intellectual equal. They think they’re smarter than the con man, not recognizing that such deception is the strength of the con man, his only profession.

19thorold

I think the real answer must be an unhelpful "it depends"...

Scientists and engineers, in my experience, are very good at spotting and rejecting nonsense if it runs contrary to some basic principle of their field. I've never come across a professional colleague who takes a pretended perpetuum mobile seriously, for instance. They don't go around saying "there are more things in heaven and earth...", they look under the table for hidden magnets or wires.

The tricky stuff that catches "experts" out is when they encounter something that looks like their own discipline but really belongs to someone else's. Electronic engineers I've known are often suckers for audiophile snake-oil: they aren't usually experts in the psychology of perception, so they don't trouble to ask whether it's really possible to hear the difference. It's only when it gets really loony (e.g. directional speaker cables) that they start to wonder.

Scientists and engineers, in my experience, are very good at spotting and rejecting nonsense if it runs contrary to some basic principle of their field. I've never come across a professional colleague who takes a pretended perpetuum mobile seriously, for instance. They don't go around saying "there are more things in heaven and earth...", they look under the table for hidden magnets or wires.

The tricky stuff that catches "experts" out is when they encounter something that looks like their own discipline but really belongs to someone else's. Electronic engineers I've known are often suckers for audiophile snake-oil: they aren't usually experts in the psychology of perception, so they don't trouble to ask whether it's really possible to hear the difference. It's only when it gets really loony (e.g. directional speaker cables) that they start to wonder.

20LolaWalser

The bizarre assertions in #1--and the title of this thread--reference "conjuring". As in--rabbits out of top hats? Which on a tap of the magic wand turn into paper roses? And/or pigeons?

Eggs out of ears and golden ducats out of noses?

Or maybe the grander stuff, the disappearing of Golden Gate Bridge and suchlike? Card tricks?

And people whose entire training and professional life consists of applied skepticism of highest degree are supposed to be more likely to believe that junk is, um, "real", than the average Joe?

If scientists are more gullible/less skeptical than anyone else, why are they less likely to be religious than anyone else?

Y-eeees--I think I can be forgiven if I LOL skeptically over that. Especially since the convo is becoming more and more of a joke.

But if y'all are serious--can we have a thread now on how subpar scientists are in bed? I don't have a smidgen of anything one could construe as "proof", but who needs that? I'm sure we can come up with some excellent ideas for why that's true!

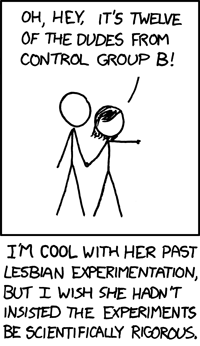

21southernbooklady

>20 LolaWalser: can we have a thread now on how subpar scientists are in bed?

Since I've only slept with scientists I can attest to the fact that they are very good in bed. Of course, I am lacking a control group, so my data has no baseline or context. Possibly my standards for what constitutes being "good in bed" are very low. ;)

Since I've only slept with scientists I can attest to the fact that they are very good in bed. Of course, I am lacking a control group, so my data has no baseline or context. Possibly my standards for what constitutes being "good in bed" are very low. ;)

23southernbooklady

Since I'm not bisexual, the data would still be skewed, I'm afraid.

27CliffordDorset

>18 MartyBrandon:

Thank you, MartyBrandon, for rescuing the baby from the bathwater that LolaWalser is keen to throw out.

I don't want to get into a comparison of numbers of Nobel Prizes, or even the length of publication lists, but I hold by my 'weird and dumb generalisation'.

I apologise for choosing what is certainly an over-simplistic title, but I could find nothing better that didn't unnecessarily steer people's thoughts.

Thank you, MartyBrandon, for rescuing the baby from the bathwater that LolaWalser is keen to throw out.

I don't want to get into a comparison of numbers of Nobel Prizes, or even the length of publication lists, but I hold by my 'weird and dumb generalisation'.

I apologise for choosing what is certainly an over-simplistic title, but I could find nothing better that didn't unnecessarily steer people's thoughts.

28darrow

I'm wondering if the gullibilty assertion is based on the stereotypical absent-minded professor. I once worked with a scientist who could be characterized that way. Brilliant in his field of expertise but socially inept, eccentric, clumsy and lacking in common sense. I would expect that he would be easily fooled by a conjuror.

29Lunar

To add an anecdote to the fray, I was at this restaurant one time that had a magician going table to table performing table magic and as a skeptic I was thinking in my head that I was going to be very observant and that with such an informal setup instead of a stage I'd have the advantage at sussing out the sleight of hand being used. I caught a few moves here and there with his less impressive tricks. But when he lifted the final tin cup in a shell game trick, which I was sure was empty of anything larger than maybe one of those sponge balls, and a whole frickin' potato plopped out I was positively stumped. Perhaps our determination not to be deceived cannot always compete with the talent of a good magician. It's like the bigger they are, the harder they fall.

30Booksloth

#29 But you still knew it was a trick (I'm assuming). There's a difference between believing some kind of miracle has taken place and knowing you've watched a trick despite not having seen how it was done. I'd like to think (to give quite a well-known example) that if I was at a wedding and someone appeared to change water into wine, I'd know it for a conjuring trick even though I wouldn't have much interest in how it had been worked. I'm beginning to wonder whether the person who made the original claim about scientists being more gullible about this kind of thing might have been confusing gullibility with a simple lack of interest in catching out the conjurer.

31jjwilson61

I'm sorry, but being a skeptic isn't just saying, "I don't care what I saw, I just don't believe it." Otherwise the non-skeptics will say "Why should we listen to you, you won't believe us no matter what." and they'd be right. If someone turned water into wine I'd hope that someone would be trying to discover how he or she did it.

33Booksloth

#31 Not the same thing at all. Anyone who saw a conjuring trick for the first time would be foolish not to wonder how it was done but after hundreds/thousands of years of conjuring tricks there really isn't much need for every one of us to investigate every single one. Life is too short. Sometimes you just have to assume the likeliest explanation and move on to more important things to spend your time on.

34Lunar

#30: Yeah, I wouldn't say being jaded to the performance of magic tricks is really part of a skeptical reaction. It's true that not every magic trick needs to be investigated, but if the trick were impressive enough I think most skeptics would not be satisfied with disdmissing it as as just another magic trick.

35pgmcc

#29 I was at this restaurant one time that had a magician going table to table performing table magic

I attended a conference dinner in the Antwerp Stock Exchange building. There was a conjuror going around the tables performing tricks that we all found entertaining and were very focused on trying to see how he was managing to do them.

Later in the evening he was presented in the centre of the dining area and we were expecting him to perform more sophisticated illusions.

He did not. It turned out his magic tricks were all for distraction. When he was presented in the centre of the room he started to produce watches, wallets and other personal items which he had managed to pick from our pockets while performing his magic tricks. He had removed items from at least three people at each table and nobody noticed anything missing until he produced them later.

I was a wonderful piece of misdirection.

I attended a conference dinner in the Antwerp Stock Exchange building. There was a conjuror going around the tables performing tricks that we all found entertaining and were very focused on trying to see how he was managing to do them.

Later in the evening he was presented in the centre of the dining area and we were expecting him to perform more sophisticated illusions.

He did not. It turned out his magic tricks were all for distraction. When he was presented in the centre of the room he started to produce watches, wallets and other personal items which he had managed to pick from our pockets while performing his magic tricks. He had removed items from at least three people at each table and nobody noticed anything missing until he produced them later.

I was a wonderful piece of misdirection.

36southernbooklady

Was his name Apollo Robbins?

I think it is entirely possible that scientists, or rationalists, are easier targets for illusionists. Scientists look at the world in predictable ways. There is a set of things that they know can happen, and a set of things they know can't happen, and they dismiss out of hand the latter. Any illusionists worth his salt knows how to take advantage of the predictable ways in which we react to what we see.

But this does not mean that a scientist is more likely than any other random person to believe that the rabbit pulled out of the hat materialized out of nowhere. He's easy to trick, perhaps, but impossible to convince.

I think it is entirely possible that scientists, or rationalists, are easier targets for illusionists. Scientists look at the world in predictable ways. There is a set of things that they know can happen, and a set of things they know can't happen, and they dismiss out of hand the latter. Any illusionists worth his salt knows how to take advantage of the predictable ways in which we react to what we see.

But this does not mean that a scientist is more likely than any other random person to believe that the rabbit pulled out of the hat materialized out of nowhere. He's easy to trick, perhaps, but impossible to convince.

37pgmcc

#36 Was his name Apollo Robbins?

Fascinating article.

My dinner experience was over 15 years ago and the man was in his fifties at that stage, so I do not think it was Robbins.

Fascinating article.

My dinner experience was over 15 years ago and the man was in his fifties at that stage, so I do not think it was Robbins.

38CliffordDorset

>30 Booksloth:

Surely a scientist, believing that what he/she witnessed was just a trick, would be compelled by his/her mind-set to prove that it was a trick. For me at least, this mind-set is the mark of being a scientist, even though low-grade teaching effectively defines science as a lot of knowledge. Regrettably.

A true scientist would want to design and execute experiments which would test whether what he/she witnessed was true or a trick, and to keep doing that until there was compelling evidence of one or the other.

I admit that in a trivial example such as 'magic' I wouldn't have the time or inclination for this, but I would wish to remember what I witnessed, and remember it, sadly shaking my head while having a strong inclination to believe it was an illusion, until such time as I had more evidence.

IMHO!

Surely a scientist, believing that what he/she witnessed was just a trick, would be compelled by his/her mind-set to prove that it was a trick. For me at least, this mind-set is the mark of being a scientist, even though low-grade teaching effectively defines science as a lot of knowledge. Regrettably.

A true scientist would want to design and execute experiments which would test whether what he/she witnessed was true or a trick, and to keep doing that until there was compelling evidence of one or the other.

I admit that in a trivial example such as 'magic' I wouldn't have the time or inclination for this, but I would wish to remember what I witnessed, and remember it, sadly shaking my head while having a strong inclination to believe it was an illusion, until such time as I had more evidence.

IMHO!

39MartyBrandon

>36 southernbooklady: Good article. Robbins reveals a few of his secrets here (http://www.slate.com/blogs/browbeat/2013/01/07/apollo_robbins_pickpockets_adam_green_reveals_his_tricks_video.html).

Realizing this is all anecdotal, I think the image we have of scientists as Holmesian logicians is part of the problem. The methodical investigation of a Gregor Mendel differs considerably from the grant-driven, "publish or perish", "science as an occupation" experience of today's researchers. While appreciative of their low-paid, laborious contribution (I spent 8 years doing research in a biomedical lab), we should recognize that the key aspect to science is the process by which it is performed. Science works because it is practiced in a culture where one must standup and subject their theories to the criticism of their peers. David Brin refers to this as an arena of ritualized combat, important because it provides a mechanism to kill off bad ideas (similar arenas exist for legislature and law). It's as if scientists have been incentivized to enter into combat in order that only the most robust truths will inform civilization. Without the arena, scientists would find it difficult to live up to the popular expectation, something that magicians and conmen may have already realized.

Realizing this is all anecdotal, I think the image we have of scientists as Holmesian logicians is part of the problem. The methodical investigation of a Gregor Mendel differs considerably from the grant-driven, "publish or perish", "science as an occupation" experience of today's researchers. While appreciative of their low-paid, laborious contribution (I spent 8 years doing research in a biomedical lab), we should recognize that the key aspect to science is the process by which it is performed. Science works because it is practiced in a culture where one must standup and subject their theories to the criticism of their peers. David Brin refers to this as an arena of ritualized combat, important because it provides a mechanism to kill off bad ideas (similar arenas exist for legislature and law). It's as if scientists have been incentivized to enter into combat in order that only the most robust truths will inform civilization. Without the arena, scientists would find it difficult to live up to the popular expectation, something that magicians and conmen may have already realized.